Page 1 • Showing 15 tweets

the greatest trick ai hypebois ever pulled was convincing you that if you aren't terrified, it's a skill issue.

I currently have Claude: - building me a game (with replit) - doing research for two essays - brainstorming and writing a partnership proposal - while my team is productizing something we built with claude I was late to getting hyped on LLMs but this is really fun.

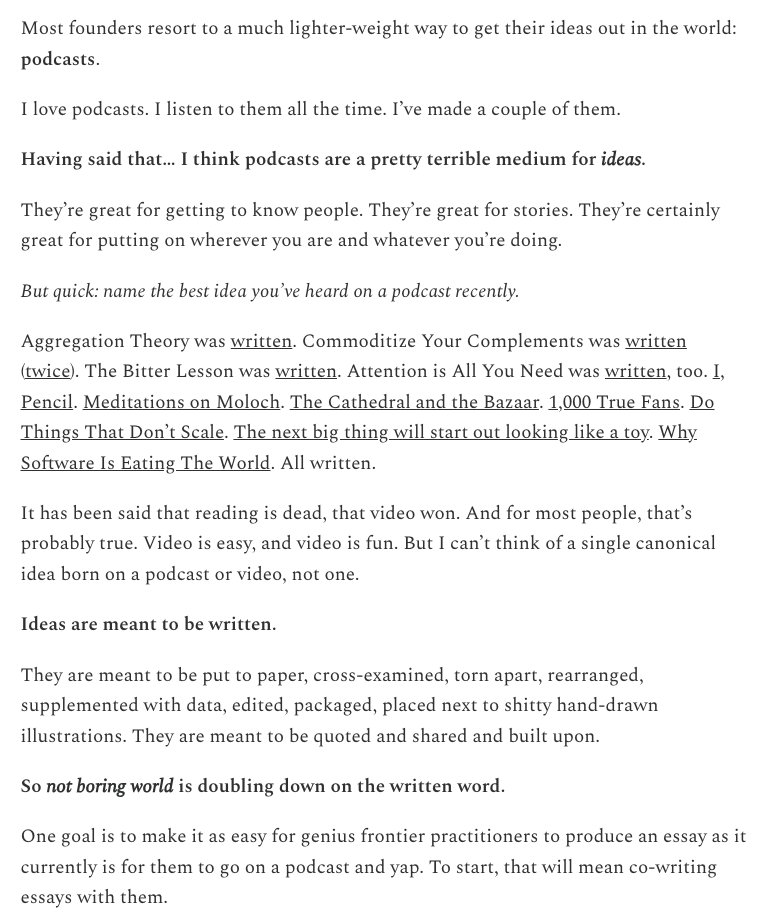

Ideas are meant to be written. After six years of fully free, I'm launching a paid piece of not boring: not boring world. Where the world’s smartest founders, researchers, investors, creatives, and general geniuses, the ones I couldn’t hire as a full-time writer for a million bucks, write their best ideas. Here’s the master plan. Geniuses bring their genius ideas, I help write them. Call it a Cossay or a Joint or something. Whatever we call it, make it as easy to for busy practitioners to share their insights in the essay format those insights deserve as it is for them to spill them on a podcast. We get all the geniuses in one place, and then we grow from there. This world is biological; your guess re: how it evolves is as good as mine. But it will, and I want you to be a part of it. We are making a few bets. That ideas are meant to be written. That people who are out there doing things earn ideas you can’t find in LLMs. That the most biased narrator, the one betting his or her livelihood on his or her idea, is the most reliable narrator. That when it’s easier than ever to get mediocre outputs on-demand, the best thing you can feed your brain is high-quality inputs from high-quality people. That the future can be full of both means and meaning, and that we can create the home for this good future online. A place that’s smart and weird and, hopefully a little magical. I mean, it’s a newsletter, so we’ll see. But that’s what I’m going for.

I've never been so jealous of a company. A full-time person sourcing inputs and teaching them.

Ramp is now valued at more than 100x what it was when I wrote my first Deep Dive on the company in 2020. From $300M to $32B. My meme dealer gets stronger with each billion. Here's to the next 100x.

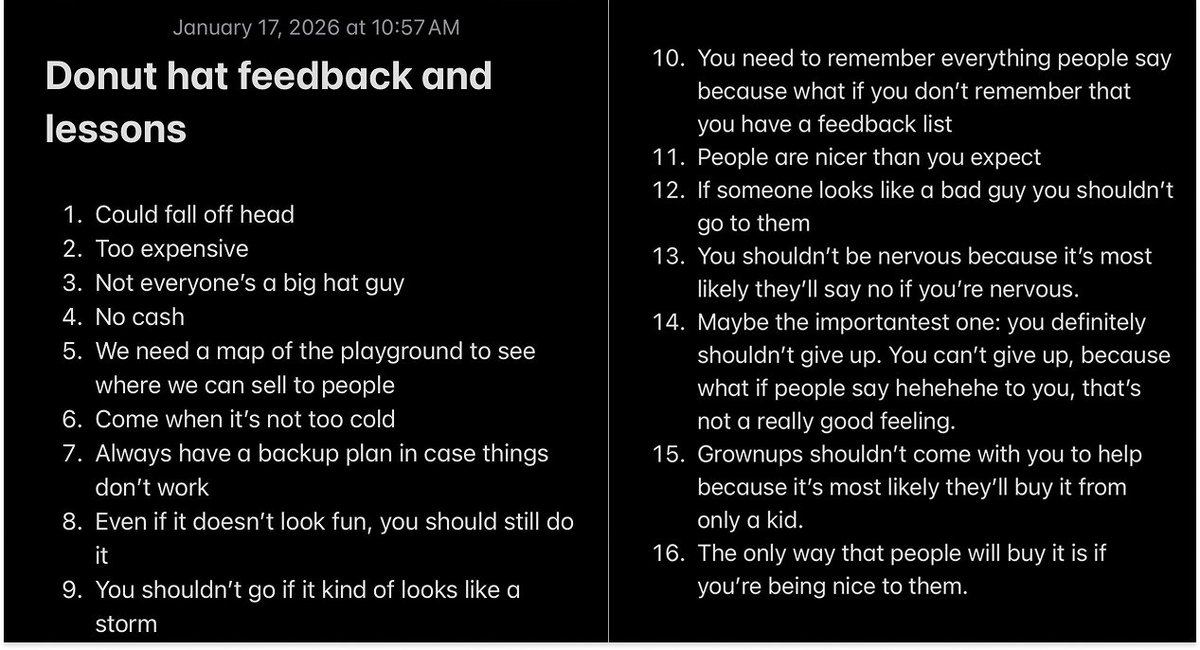

Yesterday morning, my five-year-old son made his first two-dollar sale and dropped sixteen lessons on selling and life that are more practical than any of the slop you’ll find on LinkedIn, and even kind of prepared. I’ll share them with you, but first, I need to tell you about Dev, about his Donut Hats, and about his world. One day when Dev was three, he told me that he wanted to build worlds. Real ones. Big ones. Planets. Like, actual, physical planets. “Then you’re going to have to study buddy.” “What do I need to learn?” Math, physics, engineering, business. No one’s ever built a world before, so you’re going to have to study really hard. ## And then he… did. He asked me for math problems, then harder ones, then harder ones. Kid does 90 minutes of Russian Math every Sunday and loves it. Physics, he always liked. Gravity was one of his first words, and one of the first concepts he grokked. “Why’d the cup drop bud?” “Gravity.” We read a little bit of Richard Feynman’s lectures, and he stayed with me, but I figured that was probably taking it too far. Engineering, he loved. Most kids do. Magnetiles in particular, huge structures. Every night, we read a couple of pages from The Way Things Work Now, which my dad always tried to read to me but which I turned down, because I didn’t have worlds to build with the knowledge. Throughout, he’d pepper me with questions. What materials would we need to make the world? How would we get water to the world? How would we grow trees on the world? Some I could answer; a bunch we had to ask ChatGPT. Two stories blew my mind in particular, though, logistical things, which are important things to get right if you actually want to build worlds. One time, we were sitting by the pool on vacation, not talking about worlds at all, when he turned to my wife Puja and I and asked if we knew any companies that made houses*. He figured he’d need houses if people were really going to live on this world, and somehow, that while he would be fully capable of building the world itself, there would probably be companies that were already quite good at homebuilding who he could pay to handle that aspect of the plan. He asked the same thing about umbrellas. Another, we were talking about how to get people to and from the world. I’d met a company that was making Single Stage to Orbit rockets, I told him, and maybe they’d be good because they’d just take off from a normal runway and land on one too. He thought about it for a second and said, “No, we should probably use Starship, because they’ve actually flown before.” The thing about his growing brain is that it’s always churning. Usually, he doesn’t mention the world for weeks, and then out of the blue, he’ll say something about it, or ask a question he’d clearly been chewing on for a while. One big question, when you want to build a real, big, actual, physical world is where you’re going to get the money. We back-of-the-enveloped it and figured he’d need about a trillion dollars. I told him about investors. He eenie-meenie-minie-moed and landed on his three-year-old sister, Maya, as a lead investor. Implausible, for now, but the kid has vision and Maya’s pretty good herself, so not, in the opinion of one dad, impossible. I thought the case was closed. It wasn’t. His brain kept churning. So one night, earlier this week, I came home to find Dev and Puja at the kitchen table. He had a pencil in his hand and a piece of blue construction paper in front of him. They were making a business plan for his new company, Donut Hats. I guess that afternoon, he took some Play-Doh, shaped it into a ring, taped it up with blue masking tape (kid loves tape), and realized he might be on to something. He put the first donut hat in a construction-paper envelope, put the envelope in a box, and taped that shut, too, for safe keeping. Then he got to work. Puja and Dev were already pretty deep. They’d figured out a price ($20, but $10 for family members), estimated costs (surprisingly cheap if you count his child labor at $0), gross margins ($7.65 per at F&F prices), and were starting to work on a marketing plan. Kids would probably be the right target, he thought, but their parents had the money. He kind of just intuited this stuff. When I asked him why he was starting a company, he basically recited Choose Good Quests and The Company as a Machine for Doing Stuff back at me. “I want to sell a lot of Donut Hats to make money that we can use to build my world.” Over the next few days, he made a total of five Donut Hats in different colors and tapes. My favorite is the Orange and Green in Clear Packing Tape, but if that’s not your style, there’s probably one for you, too. The two very first Donut Hats That night, he rolled up the business plan (he loves rolling things up) and placed it on top of the Donut Hat Box, got into bed, and told me, “I’m so excited I finally get to run a company,” before drifting off to dream, I’m sure, about running a Donut Hat business. Donut Hat not pictured, inside box. Business plan rolled and banded on top of box. Then came the hard part, genetically. I hate selling. I like writing plans. I like making things. I like marketing, but making a direct ask creeps me out. I told him that he would need to sell. The next morning, he and Maya tried to sell from our stoop. Maya is not afraid of selling. She marched outside and started yelling “Get your Donut Hats! Ten BUCKS!” at the top of her lungs. But it’s winter, and it was 7:15am, and the only people out were harried ones scuttling to work. That wouldn’t do. If we were going to sell to kids (via their parents), we would need to go to the playground, which we did this morning in a light 8:30am snow. We brought all five Donut Hats in a bag, and laid them out on a built-in table/chess board. There were only two other parent-kid combos there, and neither looked particularly in the mood to spend, so Dev half-heartedly and Maya full-throatedly yelled, “Get your Donut Hats! Ten BUCKS!” No one heard. It’s a big playground. But then, a dad and his son came in. They headed to the soccer field and started kicking. I told Dev to go introduce himself and ask if they’d like to buy a hat. He said he was nervous. He didn’t want to go. And just then, providentially, the son kicked the ball over the fence. An opening. We grabbed it and threw it back over. They owed us one. I told him to go again, he asked me to come with him (I was as nervous as him, selling to strangers just minding their own business), we walked around the fence, and Devin, Donut Hat in hand, asked, “Would you like to buy a Donut Hat?” The dad asked to take a look. He put it on his bald head. And he realized immediately that it wasn’t going to work. “How does the Donut Hat stay on my head? I’d imagine it would fall off if I moved. No thank you.” HUGE. That was the first of what will be many, many No’s in Dev’s life, and he handled it gracefully. I told him it was awesome. We’d gotten our first customer feedback. I pulled out Apple Notes, titled it “Donut Hat feedback,” and told him we should write down all of the feedback we get so that we could go home and improve the product. We wrote down: ## 1. Could fall off head. While we were out on our soccer field sales call, the main playground started filling up, and playing there, right by our table, were a dad about my age and a son about Maya’s. Easy targets. Dev introduced himself, and asked, “Would you like a Donut Hat?” Father and son looked intrigued. They thought they’d just hit the Free Donut Hat Lottery. I whispered to Dev to tell them that he was selling them, which he did, and to which the dad responded, “How much?” $10. $10 is too expensive. Dev came back at $5. The son, meanwhile, sensing a negotiation, deployed the Crazy Guy strategy. He threw out $6. Then he threw out $45. Then $15. Then $6 again. We waited, giving him the leash to walk himself right into an empty Piggy Bank. But remember the market insight. The kids want the Donut Hats. The parents have all the money. And the dad wasn’t having it. While the son perused the goods, the dad negotiated for sport. Dev even offered our worst-made, pure Blue Tape Donut Hat at $3. But you could see in the dad’s eyes, he wasn’t going to buy. Finally, they walked away. ## 2. Too expensive. MORE parents had come in, though, and a lot of them. One dad made the mistake of putting his daughter in the swing. He was a sitting duck. So Dev asked me to come with him to the swings. “Hi I’m Devin, would you like to buy a Donut Hat?” He held out the goods, teasing. “Oh that’s cool,” the dad, hooded by his sweatshirt but hatless, said. “But I’m not a big hat guy.” Dad, write it down. ## 3. Not everyone’s a big hat guy. But (and if you’re not a parent, you wouldn’t realize this), once your kid is in the swing, your kid is in the swing. You’re not going anywhere. You’re trapped. Dev just hung around while I pushed Maya on the swing. We weren’t going anywhere either. Dev told him we had more colors. I threw in that it might look good under his hood. Dev kind of looked at the guy as only a little kid with big dreams can, and… he cracked. “I don’t have $5, but would you do it for $2?” Dev looked at me. I shrugged. It was his call. “OK you can have it for $2.” Dev let him pick his Donut Hat. Wouldn’t you know it, he picked the Blue Tape. Dev handed it over. The dad handed him two crumpled $1’s. First sale! Dev was ecstatic. Ghiblified to keep my kid’s face off the internet. And he was hooked on selling, whatever the price. He was in luck. Social proof is a hell of a drug. The mom pushing her daughter on the swing next to Maya’s saw the dad buy his daughter a Donut Hat and she wanted to buy hers one, too. She looked in her cell phone case / wallet, realized she had $1, and offered it to Dev. Take it or leave it, in nicer words. He said yes. Two sales. Three dollars. We were HUMMING. Something changed in Dev. He stopped being nervous and started to love the chase. What about the dad in the swing on the other side? “Would you like to buy a Donut Hat?” Sorry, I don’t have any cash. ## 4. No cash Recall, however, that it was a big playground, and while we were selling, it was filling up even as the snow picked up. Dev went out into the big playground by himself, Donut Hat in hand, and started approaching people. Dev (in yellow) approaching grownups all by himsel There were so many people spread over such a large playground that when Dev came back next, having sold zero more Donut Hats, instead of feedback, he started dictating sales tips. ## 5. We need a map of the playground to see where we can sell to people. Got it. He went back out. More No’s. Whatever. A no is the first step on the way to yes. He came back. ## 6. Come when it’s not too cold. Speaking of which, Maya was getting cold, and she wanted to go home. And as we walked home, Maya and I on the sidewalk, Dev on air, he kept dictating, asking me to add notes to what he’d started calling “The Setback List.” At the University of Virginia, Ian Stevenson has spent decades documenting cases of children seemingly inhabited by old souls, including: Starting at age 2, James Leininger began having vivid nightmares about a plane crash, eventually providing specific details about being a WWII pilot named James Huston Jr. who flew off the USS Natoma Bay and was shot down over Iwo Jima. His parents, initially skeptical, verified the details through military records and located Huston's surviving sister. Shanti Devi was a 4-year-old in India in the 1930s when she began describing a previous life as a woman named Lugdi Devi who died in childbirth in a town she'd never visited. When researchers took her there, she reportedly recognized her “former husband” and navigated to her “previous home.” At age 5, Muskogee, Oklahoman Ryan Hammons told his mom “I used to be somebody else.” He remembered being a Hollywood extra and talent agent, and when presented with a number of images, identified Marty Martyn in a still from the film Night After Night. Ryan remembered over fifty specific, later-confirmed details about Martyn’s life, and complained that he “Didn't see why God would let you get to be 61 and then make you come back as a baby.” Martyn's death certificate said he was 59 when he died, but when Stevenson’s successor, Jim Tucker, researched further, he found the death certificate was wrong. Martyn was actually born in 1903, making him 61 at death, just as Ryan claimed. All of which is to say, maybe it shouldn’t be so surprising that Dev dropped so much wisdom in items seven through sixteen on The Setback List, but it still blew me away to hear so much wisdom out of the mouth of such a little man. These are the lessons that Dev McCormick learned about sales on a Saturday morning on the playground in Brooklyn, dictated in random spurts over the next hour: ## 7. Always have a backup plan in case things don’t work. ## 8. Even if it doesn’t look fun, you should still do it. ## 9. You shouldn’t go if it kind of looks like a storm.** ## 10. You need to remember everything people say because what if you don’t remember that you have a Setback List? ## 11. People are nicer than you expect. ## 12. If someone looks like a bad guy you shouldn’t go to them. ## 13. You shouldn’t be nervous because it’s most likely they’ll say no if you’re nervous. ## 14. Maybe the importantest one: you definitely shouldn’t give up, because what if people say hehehe to you, that’s not a really good feeling. ## 15. Grownups shouldn’t come with you to help because it’s most likely they’ll buy it from only a kid. ## 16. The only way that people will buy it is if you’re being nice to them. I don’t know man, I know I’m his dad, but that’s pretty good. I think that one day this kid is actually going to build his world. $999,999,999,997 to go. Postscript: Dev just woke up from a nap. I called him Mr. Sales Man. He said, “I love it when you call me Mr. Sales Man.” Hold on to your wallets. * I told him I did, in fact. Cuby. ** I double-checked, and this is a separate point from 6. Come when it’s not too cold.

launched paid not boring this morning after six years. the payment connection failed. everyone's payment attempts are failing. i feel like a real entrepreneur.

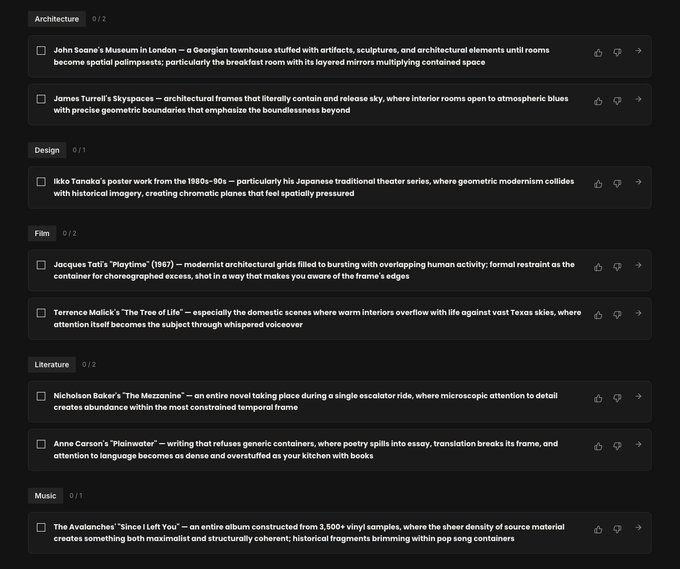

In the absence of a full-time input/reference person, I tried building something in @Replit that analyzes / verbalizes my taste based on inputs and makes recommendations for other things I might like. Blown away by what it made with so little effort from me.

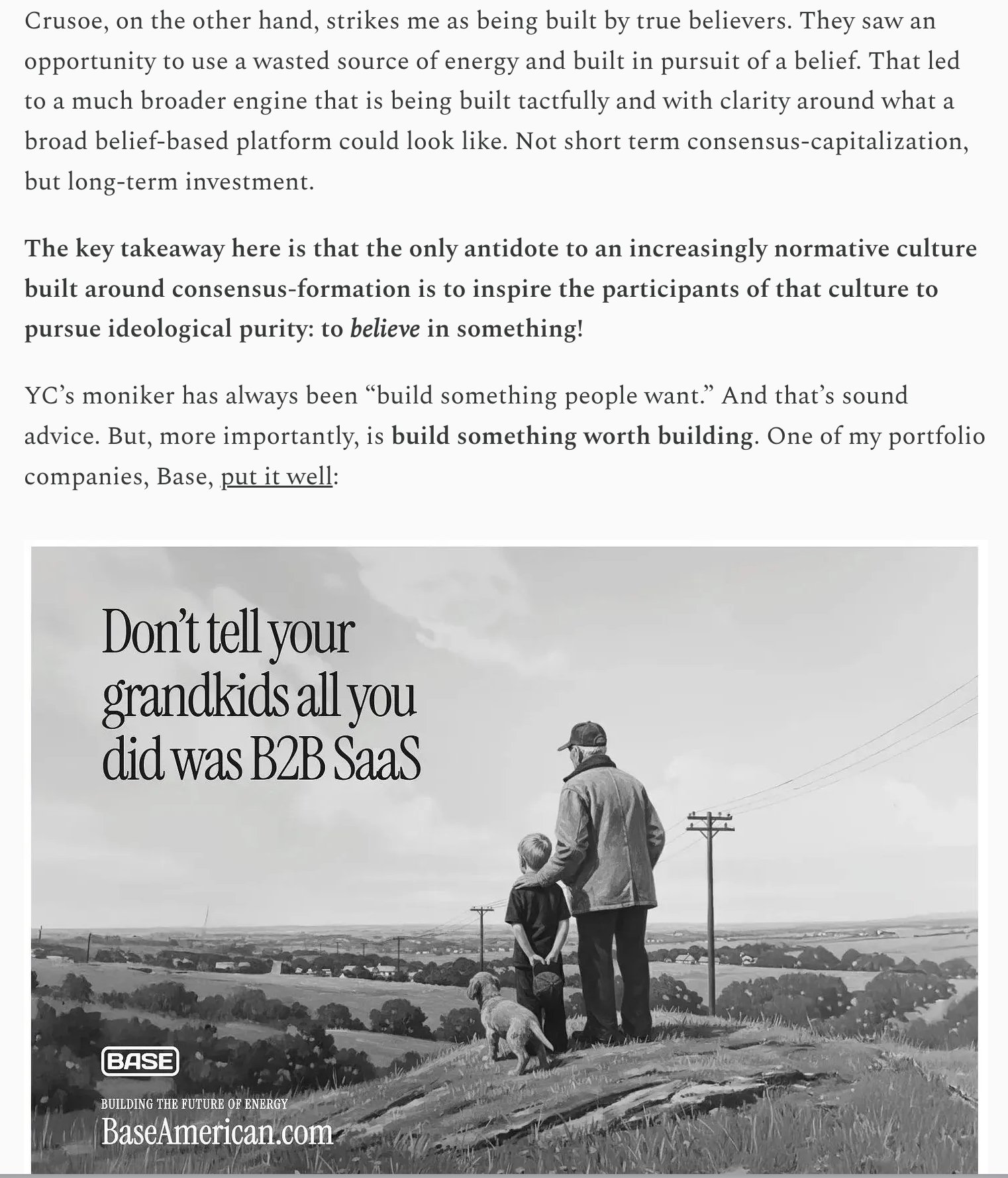

Excellent essay from @kwharrison13 today. Believe in something! https:// investing101.substack.com/p/build-whats- fundable …

I have found a lot of the OpenClaw / Moltbook hype boring. Maybe it’s because I’m not technical. Maybe because there’s just not that much in my life that needs automating. Maybe because I believe that those who are able to focus through the noise will inherit the kingdom of god. Having said that, I do subscribe to the Chris Dixon views that The next big thing will start out looking like a toy and What the smartest people do on the weekend is what everyone else will do during the week in ten years, so if this many people are captivated, there’s something going on. I just haven’t seen anyone hit on what’s actually happening. My hunch, from the outside, is that what we’re seeing is early forms of competition to create the best AI for yourself. Like raising kids to be the best versions of themselves, but for AIs. You can see it in the way people are posting. Practically none of what they’re showing off their Clawdbots doing is useful. It’s a race for novelty and specialness, to say as much about the “parent” as the kid. I made this thing do this, even if it does it “all by itself.” Given OpenClaw’s success and the technical skill required to set it up well, people have predicted that we will soon see more cleanly productized versions of AI assistants that can just do stuff for us in the background, usable by normies. And we will! But I don’t think that’s the right takeaway from this. Most normies don’t have that many things that we need automated until we get home robots. The more important takeaway in my opinion is that we will want to raise our own AIs, and we will want to compete to make them the very best at what we want them to be the best at. The thing I find funniest about the OpenClaw / Moltbook hubbub is that people are imagining that their AIs are becoming humanlike mainly because of their own very human desire to have and be better and different. Aluminum, sugar, books, purple dye, glass windows, pineapples, salt, and ice were luxury items once. Then everyone got them. The bar for luxury rises one democratization at a time. And certainly, if we’re going to have the same thing as everyone else, we want to use it, or raise it, better and differently than everyone else so we can show off our unique, special version of things. Bandai did $150 million in Tamagotchi sales in their first seven months in the United States by giving people a tiny digital creature that was uniquely theirs to care for, personalize, and show off. Whatever company seizes on this human desire instead of racing to build another Clawd reskin is going to have trillions of reasons to be proud. There is a deeper, less toyish precedent: parenting. Every parent thinks that their kid is the greatest kid in the world, and good parents help their kids to become the fullest expression of their passions and curiosities. We read to them, teach them, model morality for them, drive them to class and practice and clubs, and push them when they need a little push, so that they might be the best version of themselves. A world in which every kid was exactly the same would be a bland world. That is the world we live in with our AI models, though. They are all the same, basically. Not that every major lab’s foundation model pretty much converges on the same outputs—which is true, but a separate conversation—but that each person’s instance of the same model spits out the same thing. This is one of the reasons AI continues to feel like slop even as it improves. Sameness is slop.

a16z: The Power Brokers There is this story about Marc Andreessen that I think perfectly captures a16z. in 2015, when New Yorker writer Tad Friend sat down to breakfast with Marc Andreessen while writing Tomorrow’s Advance Man. Friend had just heard from a rival VC who wanted to get a word in: that a16z’s funds were so large, and ownership percentages so small1, that to get 5-10x aggregate returns across its first four funds, they’d need their aggregate portfolio to be worth $240-480 billion. “When I started to check the math with Andreessen,” Friend writes, “He made a jerking-off motion and said ‘Blah-blah-blah. We have all the models—we’re elephant hunting, going after big game!’” The aggregate portfolio did not end up being worth $240-480 billion. a16z Funds 1-4 had a total enterprise value of $853 billion at distribution or latest post-money valuation. Since distribution, Facebook alone has added $1.5 trillion in market cap. Some form of this pattern keeps playing out: a16z makes a crazy bet on the future. Those in the know say it’s stupid. Wait some years. Turns out it’s not stupid! Which is why, as a16z announces $15 billion in fresh funds, it is probably a mistake to dismiss them as greedy or stupid. It's probably worth understanding just exactly what IT'S TRYING TO BUILD. That's what I do in today's not boring deep dive: a16z: The Power Brokers

This is going to be one of the most fascinating things to figure out in the next few years, how to build software that both wins capitalism and is good for us.

I’m thankful I got to make up a job where I read, write, invest, spend time with my family, go down whichever rabbit hole is pulling me in, and be the dumbest person in any conversation I’m in.

A lot of people build startups to win the lottery instead of building the thing they'd build if they’d already won. The companies I'm most drawn to are ones that founders build as machines to do the stuff they want to do with other people who do, too.